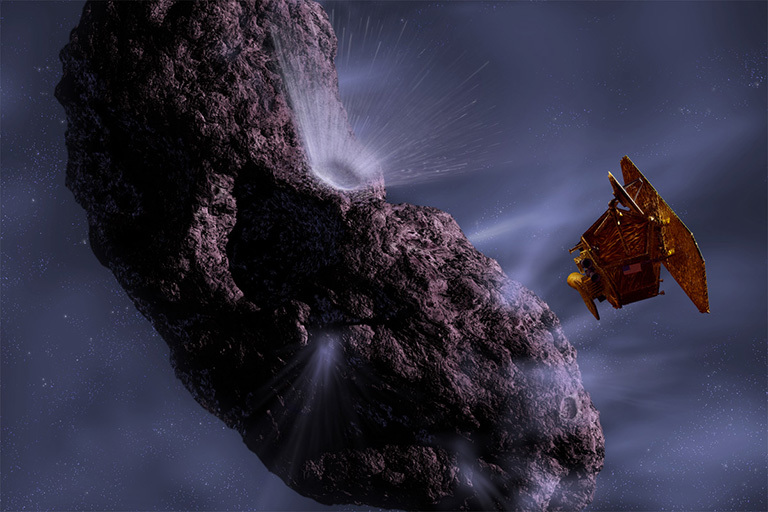

When the gravity maps and magnetic anomalies were compared, Penfield described a shallow "bullseye", 180 km (110 mi) in diameter, appearing on the otherwise non-magnetic and uniform surroundings-clear evidence to him of an impact feature. He then obtained onshore gravity data from the 1940s. In the offshore magnetic data, Penfield noted anomalies whose depth he estimated and mapped. : 20–1 Penfield's job was to use geophysical data to scout possible locations for oil drilling. In 1978, geophysicists Glen Penfield and Antonio Camargo were working for the Mexican state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos ( Pemex) as part of an airborne magnetic survey of the Gulf of Mexico north of the Yucatán Peninsula. The impact spewed hundreds of billions of tons of sulfur into the atmosphere, producing a worldwide blackout and freezing temperatures which persisted for at least a decade. The aftermath of this immense asteroid collision, which occurred approximately 66 million years ago, is believed to have caused the mass extinction of non-avian dinosaurs and many other species on Earth. : 83–84 Artistic impression of the asteroid slamming into tropical, shallow seas of the sulfur-rich Yucatán Peninsula in what is today Southeast Mexico. Unknown to them, evidence of the crater they were looking for was being presented the same week, and would be largely missed by the scientific community. Recognizing the scope of the work, Lee Hunt and Lee Silver organized a cross-discipline meeting in Snowbird, Utah, in 1981.

: 82 There were no known impact craters that were the right age and size, spurring a search for a suitable candidate. Their paper was followed by other reports of similar iridium spikes at the K–Pg boundary across the globe, and sparked wide interest in the cause of the K–Pg extinction over 2,000 papers were published in the 1980s on the topic. The Alvarezes, joined by Frank Asaro and Helen Michel from University of California, Berkeley, published their paper on the iridium anomaly in Science in June 1980. : 1095 The Alvarezes' impact hypothesis was rejected by many paleontologists, who believed that the lack of fossils found close to the K–Pg boundary-the "three-meter problem"-suggested a more gradual die-off of fossil species. At the time, there was no consensus on what caused the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction and the boundary layer, with theories including a nearby supernova, climate change, or a geomagnetic reversal. It was hypothesized that the iridium was spread into the atmosphere when the impactor was vaporized and settled across Earth's surface among other material thrown up by the impact, producing the layer of iridium-enriched clay. Iridium levels in this layer were as much as 160 times above the background level. The Alvarezes and colleagues reported that it contained an abnormally high concentration of iridium, a chemical element rare on Earth but common in asteroids. The main evidence of such an impact was contained in a thin layer of clay present in the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–Pg boundary) in Gubbio, Italy. In the late 1970s, geologist Walter Alvarez and his father, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Luis Walter Alvarez, put forth their theory that the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction was caused by an impact event. It is now widely accepted that the resulting devastation and climate disruption was the cause of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, a mass extinction of 75% of plant and animal species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The date of the impact coincides with the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (commonly known as the K–Pg or K–T boundary).

Evidence for the crater's impact origin includes shocked quartz, a gravity anomaly, and tektites in surrounding areas. Hildebrand in 1990, Penfield obtained samples that suggested it was an impact feature. Penfield was initially unable to obtain evidence that the geological feature was a crater and gave up his search. The crater was discovered by Antonio Camargo and Glen Penfield, geophysicists who had been looking for petroleum in the Yucatán Peninsula during the late 1970s. It is the second largest confirmed impact structure on Earth, and the only one whose peak ring is intact and directly accessible for scientific research. The crater is estimated to be 180 kilometers (110 miles) in diameter and 20 kilometers (12 miles) in depth. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large asteroid, about ten kilometers (six miles) in diameter, struck Earth. Its center is offshore, but the crater is named after the onshore community of Chicxulub Pueblo. The Chicxulub crater ( IPA: i) is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Chicxulub crater (Mexico) Show map of Mexico

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)